Born in 1879, the civil rights lawyer Buck Colbert (B.C.) Franklin moved from the all-Black Oklahoma town of Rentiesville to Tulsa in 1921. He set up his law practice in Greenwood. His wife and children (including 6-year-old John Hope Franklin, the preeminent historian and founding chair of NMAAHC’s Scholarly Advisory Committee) planned to join him at the end of May.

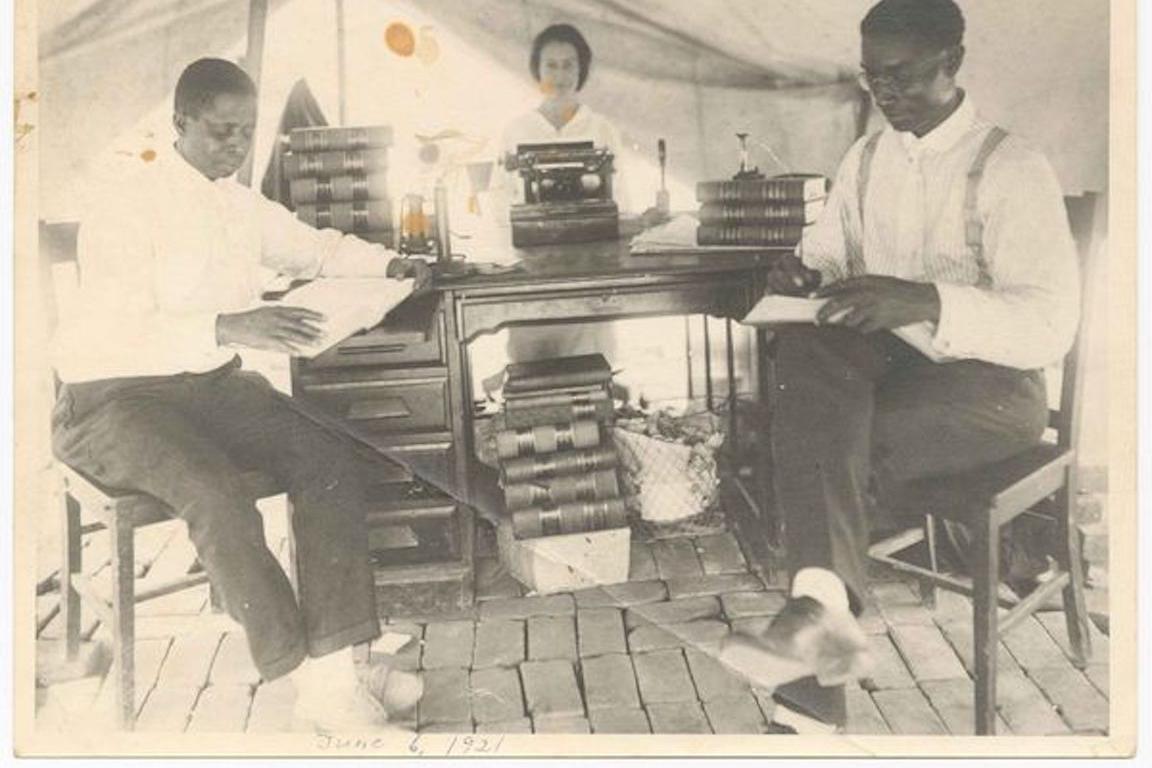

The massacre delayed the family’s arrival in Tulsa for four years. After his office was destroyed, Franklin practiced with his law partner I.H. Spears from a Red Cross tent erected in the midst of the still-smoldering ruins. One of his most instrumental successes was challenging a new law that would have prevented residents of Greenwood from rebuilding their property destroyed by the fire. “While the ashes were still hot from the holocaust,” Franklin wrote, “. . . we instituted dozens of lawsuits against certain fire insurance companies . . . but . . . no recovery was possible.”

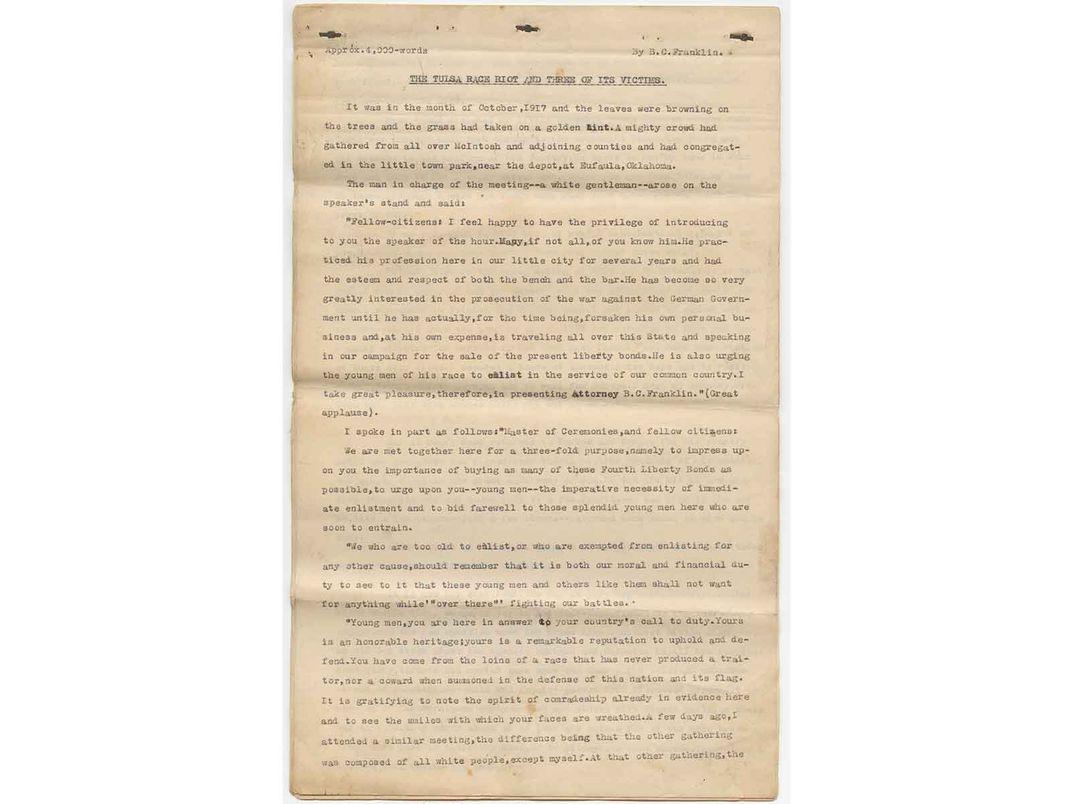

Franklin and Spears rescued Greenwood’s future as a Black community by successfully arguing that residents should be able to rebuild with whatever materials they had on hand. While Franklin’s legal legacy is secured and recorded within the dozens of suits and briefs filed on behalf of his clients, his talent in recording this pivotal event in American history has been unrecognized. His unpublished manuscript, written in 1931, was uncovered only in 2015, and is now held in the museum’s collections. Merely ten pages long, “The Tulsa Race Riot and Three of Its Victims” is a profound document.

Objects and oral histories have pushed the city and the nation toward a more truthful understanding of the past. Franklin’s manuscript is a foundational part of that process of factually bearing witness, but it is also more than just evidentiary; it is a meditation and evocation that performs at the intersection of memory, history and literature.

Franklin’s memoir is structured around three moments, detailing encounters with an African American veteran, surnamed Ross. It begins in 1918, soon after World War I, when Ross is angry because of his treatment despite his military service; it proceeds to an account of Ross defending home and family in 1921 during the massacre, and ends ten years later with his life in tatters and his mind in ruins. By choosing to center on a Black veteran, Franklin crafts a deep analysis on patriotism, disillusionment and ultimately trauma, threading a connection of the story of the Tulsa massacre to the nation’s broader story of the betrayal of those willing to sacrifice all for a nation that refuses to respect them.

Depicting encounters with Ross that traverse nearly 15 years, Franklin breaks free of some of the conventions that frame the typical survivor’s testimony, which rely mostly on recounting the events directly surrounding the massacre. Yet his eyewitness perspective, too, is filled with rich detail that describes the defense of Greenwood by its Black citizens, debates about violence and how best to make change. The eyewitness account of “planes circling in mid-air” dropping incendiary devices to burn Greenwood to its roots is a searing indictment of the white mob and its cruelty.

Franklin provides a masterful account of how the massacre crystallizes core elements of the Black experience in America and how that experience can be embodied in a single life on a single day: “During that bloody day, I lived a thousand years in the spirit at least,” Franklin recounts:

I lived the whole experiences of the Race; the experiences of royal ancestry beyond the sea; experiences of the slave ships on their first voyage to America with their human cargo; experiences of American slavery and its concomitant evils; experiences of loyalty and devotion of the Race to this nation and its flag in war and in peace; and I thought of Ross back yonder, out yonder, in his last stand, no doubt, for the protection of home and fire side and of old Mother Ross left homeless in the even-tide of her life. I thought of the place the preachers call hell and wondered seriously if there was such a mystical place—it appeared, in this surrounding—that the only hell was the hell on this earth, such as the Race was then passing through.

In his coda, Franklin combines the danger of both racial violence and the effects of choosing to forget its victims, writing plaintively of Ross, his wife and mother:

How the years have flown and how changed and changing is the whole face of this nation. It is now August 22nd, 1931 as this is being written. A little more than ten years have passed under the bridge of time since the great holocaust here. Young Ross, the veteran of the world war, survived the great catastrophe, but lost both his mind and eye sights in the fires that destroyed his home. With a burned and scared face and a mindless mind, he sits today in the asylum of this State and stares blankly into space. At the corner of North Greenwood and East Easton, sits Mother Ross with her tin cup in hand, begging alms of the passers-by. They are nearly all new comers and have no knowledge of her tragic past, hence they pay her little attention. Young Mrs. Ross is working and doing the best she can to carry on in these times of depression. She divides her visits between her mother-in-law and her husband at the asylum. Of course, he has not the slightest recollection of her or of his mother. All yesteryears are only blank pieces of paper to him. He cannot remember one thing in the living, breathing, throbbing present.

In collecting Tulsa and in telling this story, the museum’s job is to help us learn that we must not be passers-by. That in remembering lies responsibility and re-adjusting our values. That the objects we collect contain histories with a chance to change us. It is in our process of collecting with an effort to fill the silences that our institutions can become more than shrines full of static artifacts and sheaths of paper in a nation’s attic but places with the potential to be genuinely transformative and a force for truth telling, for healing, for reckoning and for renewal. Places where justice and reconciliation are paired in a process as natural as living and breathing.